In the past few weeks alone, the United States has witnessed various climate hazards and disasters affecting vulnerable communities and straining public infrastructure and housing. Extreme heat waves are endangering lives in the South and putting immense pressure on power grids. Wildfires and tornadoes threaten rural Midwest communities, while parts of New England experienced historic heavy rain and flash flooding, destroying homes and bridges. Low-income and communities of color are disproportionately impacted by climate disasters due to persistent underinvestment in infrastructure and resilience. A recent federal law and accompanying mapping tool aims to change that.

The Community Disaster Resilience Zones Act

On December 20, 2022, President Biden signed into law the Community Disaster Resilience Zones Act which will identify top communities at risk of natural hazards and disasters and provide technical support and financial assistance for mitigation and resilience projects. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has issued a request for information and is seeking public input on a tool that will be used to identify which communities will receive this designation. The request for information closes on July 25, 2023

Among other things, this law does the following:

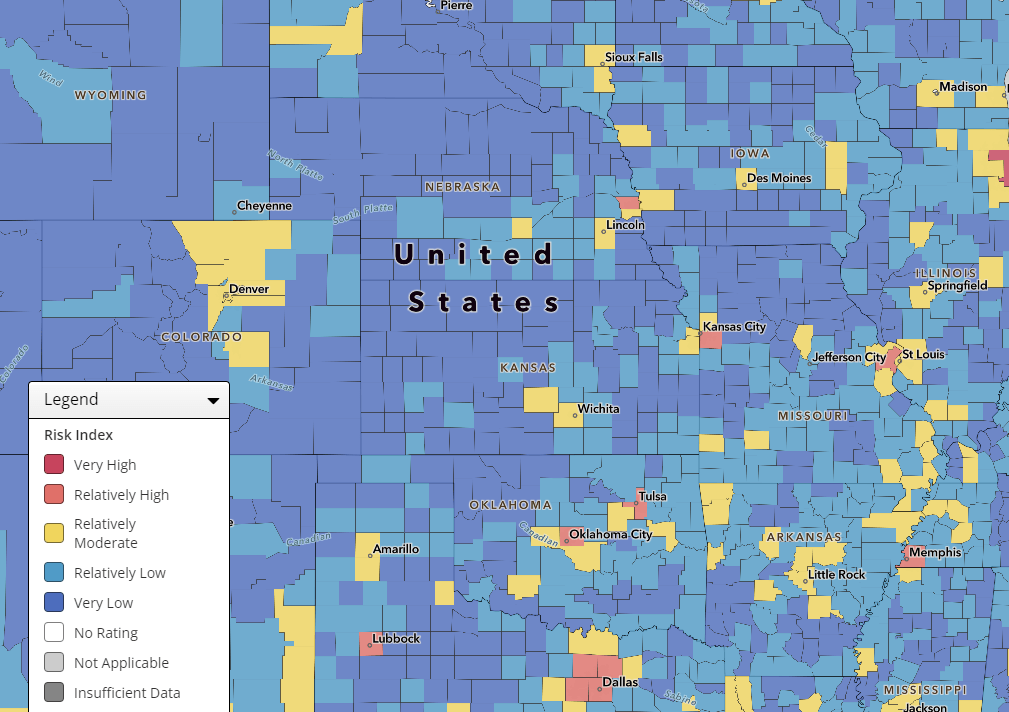

- Makes FEMA’s National Risk Index (NRI) permanent, which is a mapping tool to show the natural hazard risks across the United States by calculating the following:

- Loss exposure around population, buildings, and agriculture

- Social vulnerability

- Community resilience

- And other topics determined by the President

- Establishes the Community Disaster Resilience Zones designation

- Identifies top 50 census tracts and no less than 1% of census tract in each State with highest risk ratings

- Recommends geographic balance and representation in Tribal lands

- Establishes the designation for 5 years before reassessment of new zones

- Benefits to communities designated as Community Disaster Resilience Zones

- Prioritization for mitigation and resilience funding

- Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grant federal cost share from 75% to 90%

- Additional technical assistance and capacity building

The funding for Community Disaster Resilience Zones will come from the Disaster Relief Fund as authorized by Stafford Act Section 203 (i). While the exact amount is unspecified, the Congressional Budget Office estimates an increase in direct spending of $27 million over the next 5 years. This funding is supplementary to the existing yearly funds allocated to BRIC, which amounted to $2,295 billion for mitigation and resilience projects in 2022. Eligible applicants for resilience funding include States, Indian tribal governments, and local governments.

Potential Impact for Frontline Communities

To best serve frontline communities, it is important for FEMA to develop and utilize accurate tools when determining which communities are at highest risk of natural hazards. Historically, low-income and communities of color have received less federal disaster assistance although they are most exposed to natural hazards and experience greater impacts. Peer-review scientific studies have evaluated federal programs such as FEMA’s Public Assistance, Individual Assistance, and Hazard Mitigation Assistance and HUD’s Community Development Block Grant DR and have identified deep inequities. This is also true for the BRIC, which is participating in Justice40 and has a declared equity focus, yet the last two years has primarily benefited wealthier communities.

Part of this inequity is the persisting low investment in frontline communities which means their physical infrastructure and housing stock has lower property value and thus is replaced by smaller federal dollar amounts, which further exacerbates future impacts and inequities. FEMA damage assessments as well as appraisal inspections tend to undervalue property owned by households of color. In addition, many frontline communities do not have the capacities and tools to navigate these federal programs. BRIC explicitly requires a FEMA-approved mitigation plan prior to receiving implementation funds. Thus the CDRZA can really benefit frontline communities through the increased federal match from 75% to 90% especially for localities with limited economic resources, as well as benefit with additional technical assistance and capacity building. That is assuming it goes to communities in need, which will now be determined by FEMA’s National Resilience Index.

Threats to Frontline Communities – NRI critiques

In our initial review of FEMA’s National Risk Index (NRI) there are a number of shortcomings that will exclude many high-risk, low income communities. As it stands, the NRI calculates higher risk ratings for wealthier communities, business and industrial areas, and thus receive higher prioritization designation than frontline communities. Part of the issue is that the NRI places significant weight on property market value in its determination of hazard exposure and potential disaster losses. In other words, the higher the value of the property the greater the calculated disaster loss, thus the greater the risk score. However, such emphasis on market value replicates systemic racism and economic marginalization caused by unfair housing policies, local government’s disinvestment in low-income communities of color, and policymakers placing more value on property than on human lives and standard of living especially for Frontline communities. As part of the exposure formula, low-valued property in low-income communities should be prioritized to mitigate historic disinvestment and environmental injustice.

One major gap in the development implementation of NRI is that it excludes the total national risk rating for US Territories of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands due to missing community resilience and social vulnerability data. Yet Puerto Rico and many of these island communities consistently experience major hurricanes, face tremendous barriers to FEMA assistance, and have consistently higher recovery needs. This gap needs to be addressed immediately before the designation of Community Disaster Resilience Zones. Funding that is used to maintain and update the NRI should be prioritized to develop equivalent data for the territories as compared to the states for complete risk scores.

Another limitation is the use of external indexes for measuring social vulnerability and community resilience which were designed by other institutions and not necessarily with the purpose of identifying equitable allocations of federal disaster assistance and mitigation. There are still many limitations on these indexes and there is a need for ground truthing and validation before using composite indexes for resource allocation. Instead, FEMA should invest in collecting its own disaster applicant data and make it publicly available which would better identify communities impacted by disasters, which communities have been traditionally denied and why, and provide a better understanding of community needs around resilience, mitigation, and recovery. Importantly, FEMA should track and report on applicant’s race/ethnicity, income, and reasons of why applications are denied or approved. This would better help advocates and the agency address equity issues.

Finally, a general critique of the Community Disaster Resilience Zones Act of 2022 and BRIC grant program is the overall emphasis on physical infrastructure and mitigation as the only “building resilience” approach eligible for funding. There is a need to also support the building of social and community resilience and adaptation, especially within the Community Disaster Resilience Zones in frontline communities. Examples of social and community resilience include programs that develop community-led resilience teams, provide support to local community organizations active in disasters (COADs), and other community network-building programs and organizing efforts. Investing in social and community resilience in concert with physical resilience and mitigation projects is essential to reduce the risk of greenlining and displacement of frontline communities. When frontline communities’ physical locations are invested in without direct investment in the people too, the risk of gentrification and displacement increases.

Input on the NRI Due by July 25th

The National Resilience Index might have a broader impact beyond BRIC funding. It is likely to inform several of FEMA’s other disaster recovery and response programs and local governments will be encouraged to use it for determining where to make mitigation and resilience efforts. Thus, the potential impact of the NRI goes beyond the Community Disaster Resilience Zone Act. It is important to advocate for an accurate tool that can properly identify communities of highest need of disaster resilience and mitigation funding. Review the National Resilience Index and provide your input in the request for information here.

In addition, it is written into the Community Disaster Resilience Zones Act that the National Risk Index is evaluated and reviewed at least every five years with regard to its data, methodologies and formulas. Advocates should be on the lookout for states and localities using the NRI to make funding and project decisions, and whenever necessary provide more accurate data or insights to reduce misinformed investments. For example, due to the overemphasis on property value, the Lower Ninth Ward in Louisiana is calculated as having a relatively low risk by the NRI tool. This community is primarily a black and low-income community and was among the most affected by Hurricane Katrina and continues to lack physical infrastructure investments to reduce climate disaster impacts. We recommend FEMA to ground-truth this index with meaningful involvement of frontline communities across the United States in the development of this tool. For now, localities should leverage, whenever possible, more accurate and local data for resource allocation decisions.