The passing of President Jimmy Carter has brought about a renewed interest in 1970’s energy issues, like lines at gas stations, solar panels on the White House, and putting on a cardigan. Some look back with nostalgia at Carter as a strong voice for energy conservation with unique moral clarity. Others see him as politically naïve and unable to deliver. In either case, he poured the foundation for the energy policy and politics that we are building on today.

While energy technology has advanced, many of the questions raised by President Carter’s energy efforts remain contested. Clearly, the narrative Carter offered of personal sacrifice for the common good is waning, while the message of energy opportunity is ascendant. But the politics of energy conservation has largely been ignored in recent decades, while politics of carbon energy supply have dominated. Many greenhouse gas reductions models still take energy demand as a factor of technology and industry alone, rather than something that can be socially determined. Clearly there’s work to do to build on Carter’s vision, but there are signs of progress.

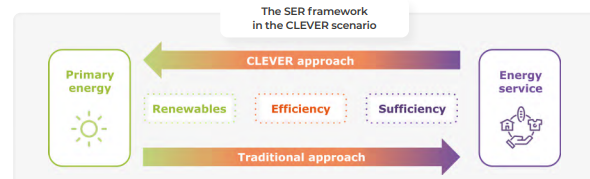

In Europe a growing effort exists to understand all the levers that can be pulled to reduce energy demand as a tool to support decarbonization. A European modeling and policy project called CLEVER (a Collaborative Low Energy Vision for the European Region) rolled out a body of work in 2023 that showed “energy sufficiency” strategies could reduce energy demand to 20-30% in France, Germany, and the UK, within a multi-strategy approach of sufficiency, efficiency, and renewables. The illustration here shows their approach of starting with energy services needed, rather than energy supplies available.

The idea of “energy sufficiency” asserts that energy – literally, “the ability to do work” – is generated and consumed for some purpose. Understanding that purpose better – and dialing-in on how to meet it with less energy – means there may be less work to do, and less energy demand. While subtle, it echoes the profound call Carter made to Americans to refocus on maximizing purpose above consumption. A message aimed at our energy use, and beyond.

Energy sufficiency strategies – many of which exist today – like right-sized, location efficient housing, transportation demand management, and agro-ecology – have higher potential to be “no-regret.” They can ease electrification, require less capital and payoff to financiers, create more opportunities for social co-benefits, and avoid resource conflicts such as mining, transmission lines, or hazardous waste required by growing energy supply. They can create easier wins for frontline communities and the climate.

A 2022 Stanford study titled Human well-being and per capita energy use found that, across nine metrics of health, economic, and environmental, more energy use aligns with social benefits at lower levels. But after certain points, more energy does not align with significant outcomes like better life expectancy, sanitation, infant mortality, and income equality. The study suggests that distributed equitably, energy average consumption of 79 GJ person globally could, in principle, allow everyone on Earth to realize 95% or more of the best performance across all metrics of wellbeing. Of course energy is not distributed equitably, not between countries or within them. But the report sheds light on the attention needed in equitably and effectively managing demand.

| Well-Being Metric | Energy Required at 95% of observed values |

| Access to electricity (%) | 12 |

| Air quality | 125 |

| Food supply (kcal day−1) | 70 |

| Gini coefficient | 28 |

| Happiness | 51 |

| Infant mortality | 24 |

| Life expectancy (years) | 30 |

| Prosperity | 75 |

| Sanitation (%) | 15 |

The good news is we may be headed in the right direction in some respects. According to the International Energy Agency World Energy Outlook, energy per capita is falling globally due to technological progress driven by policies like energy performance standards, changes in the global economy away from energy intensive industries towards services, and the efficiency of renewables and electrification with less waste heat. Still, the prediction for final global energy consumption – what counts for the climate and decarbonization – could increase by nearly 20% or decline by 15% depending on the assumptions. Whether we can intentionally reduce demand through strategies like energy sufficiency may be a key different maker in our climate justice trajectory.

The energy conversation policy discourse has made great strides since the Carter presidency. Carter laid out a challenge to all Americans to conserve energy and to focus on our energy use on a higher purpose. We should recognize his leadership on this issue, and still have plenty of work to do on nuts and bolts strategies from his era, like weatherizing buildings. But a new generation of ideas on energy sufficiency is also here. The possibility of meeting our needs with less energy demand should be an attractive proposition for everyone working on climate justice.