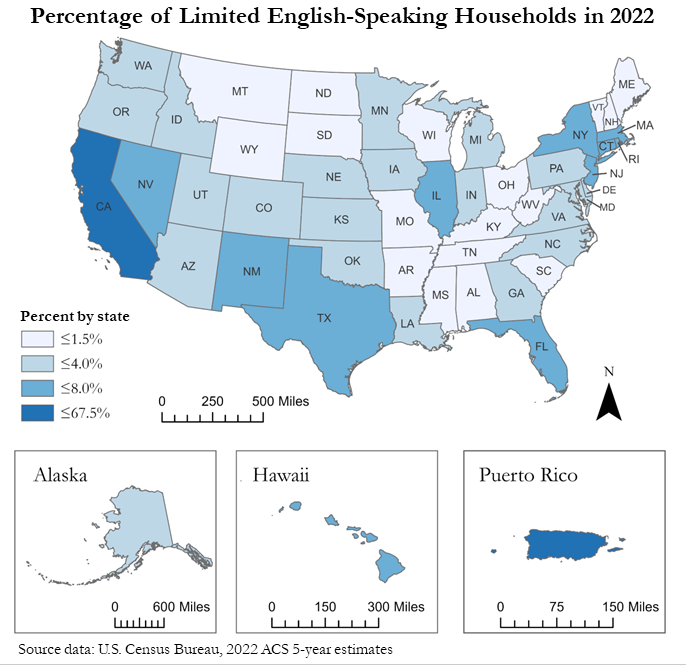

In the face of climate-related disasters, effective communication around evacuation orders and recovery resources can mean the difference between life and death. Unfortunately, individuals with Limited English Proficiency (LEP), who are at the front lines of climate change and climate-related disasters, are often excluded from these lifesaving communications— further compounding their vulnerability to climate change.

Last month, when Hurricane Beryl passed through Houston, Asian, Arabic, and Somali speaking immigrants did not receive translated evacuation orders from the city. In the first weeks after Hurricane Fiona in 2022, Puerto Ricans waited an average of 6 hours for services translating desperately needed information for disaster relief. In September 2022, when Typhoon Merbok destroyed subsistence fishing communities in Alaska, federal recovery resources translated to Alaska Native languages were completely incorrect. These are just three of many examples of demonstrating how individuals with LEP— who may include immigrants and refugees, indigenous speakers, heritage speakers, and differently abled individuals with hearing, speaking, or literacy impairments— are left behind from lifesaving communication.

Individuals with LEP should all have the same opportunity for safety, protection of life, and recovery from the impacts of climate change and climate-related disasters. In addition, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination based on national origin, which courts have interpreted to include discrimination based on English proficiency. However, the examples above illustrate that individuals with LEP face systematic challenges accessing critical information before, during, and after disasters.

Fortunately, states like New York and Hawaii are pioneering legislative efforts to enhance language access during emergencies and disasters. These models offer a crucial template for other states, demonstrating how targeted policy and funding can ensure that language is not a barrier to safety and disaster resilience.

Two Models For Addressing Language Access In Emergency Management

New York: Statewide Model

Few states have comprehensive statewide language access policies and frameworks. New York is one of these exceptions. They have established an Office of Language Access and recently expanded its language access policy. This policy directs all state agencies providing public services to translate vital documents into the top 12 most common languages spoken by LEP New Yorkers, designates a language access coordinator in each agency, and requires the development and bi-annual revision of language access plans. It also establishes a mechanism for reporting each agency’s progress and compliance with the language access law.

New York’s Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services is covered under this law, and they published their Language Access Plan in 2022. In this document, New York State Homeland Security & Emergency Services agency states their total language access budget is on average between $100,00 and $150,000 annually, and may use supplemental budgets for language access during emergencies. The plan also communicates how cultural competency and quality control are embedded as part of language access services.

Hawaiʻi: Statewide Model + Department Specific Policy

Hawaiʻi serves as a second model in that it has also created a department specific language access policy within their state’s emergency management agency. In 2006, Hawaiʻi passed their statewide language access law, which established the Office of Language Access. However, the Maui Wildfires of August 8, 2023, demonstrated the urgent need for deeper investment in language access specifically within emergency management.

The death toll from the Maui fire reached 102, of which at least 16 were foreign-born residents.1 Advocates from Roots Reborn Lahaina reported that although one out of nine people living in Hawaiʻi has limited English proficiency, there was a lack of state-coordinated language access before, during, and after the disaster. This lack of language access not only limited the evacuation capacity of LEP speakers but also hindered their long-term recovery, as official information on recovery resources was not translated to all the relevant languages.

Advocates on the ground, such as Hawaii Coalition for Immigrant Rights and Pacific Gateway Center, helped pass a unique bill designed to increase the climate and disaster resilience of LEP communities. HB2107, which became law last month, appropriates $200,000 from the state’s general revenues for the fiscal year 2024-2025 to:

- Establish a full-time LEP Language Access Coordinator position within the Hawaiʻi Emergency Management Agency; and

- Fund programming support for LEP community projects, such as public service announcements, translation services, and other initiatives.

In an interview with Just Solutions, James DS. Barros, the Administrator of the Hawaiʻi Emergency Management Agency emphasized the critical role the new Language Access Coordinator will play in positioning the State’s Emergency Management Agency to proactively address language access needs ahead of the next disaster. For example, the Administrator shared emergency management was unaware of the significant Latine community in Lahaina that needed Spanish translation during the 2023 wildfires, and the new dedicated role would help identify these needs ahead of time.2 In implementing the new law, the Administrator highlighted three major components:

- The Language Access Coordinator will be embedded in emergency management operations to guide the development of emergency management plans, communication plans, evacuation plans, and other operations. This integration will help identify language needs during the planning stages rather than encountering these needs in the middle of an active disaster.

- The Language Access Coordinator will act as the point of contact with the broader network of Hawaiʻi’s language access, immigrant/migrant, and community-serving organizations that provide not only translation and interpretation services, but also culturally relevant resources and community-embedded knowledge.

- Funding will support LEP community projects to enhance resources and collaboration across the language access network and improve Hawaiʻi’s overall capacity to serve LEP communities.

By leveraging and coordinating the existing network of Hawaiʻi’s language access and immigrant/migrant rights services, emergency management will more effectively serve LEP communities. This HB2107 bill also serves as a unique model in that it provides direct funding to create a staff position. Most other language access policies do not provide direct appropriations.

Other Considerations for Language Access Policy

In the context of climate change and language justice there are three policy recommendations that should be considered:

- Tracking emerging languages as climate migration increases.

- Building trust and embedding cultural competence in emergency management.

- Measuring translation performance based on accuracy, speed, and literacy accessibility.

Climate Migration and Emerging Non-English Languages

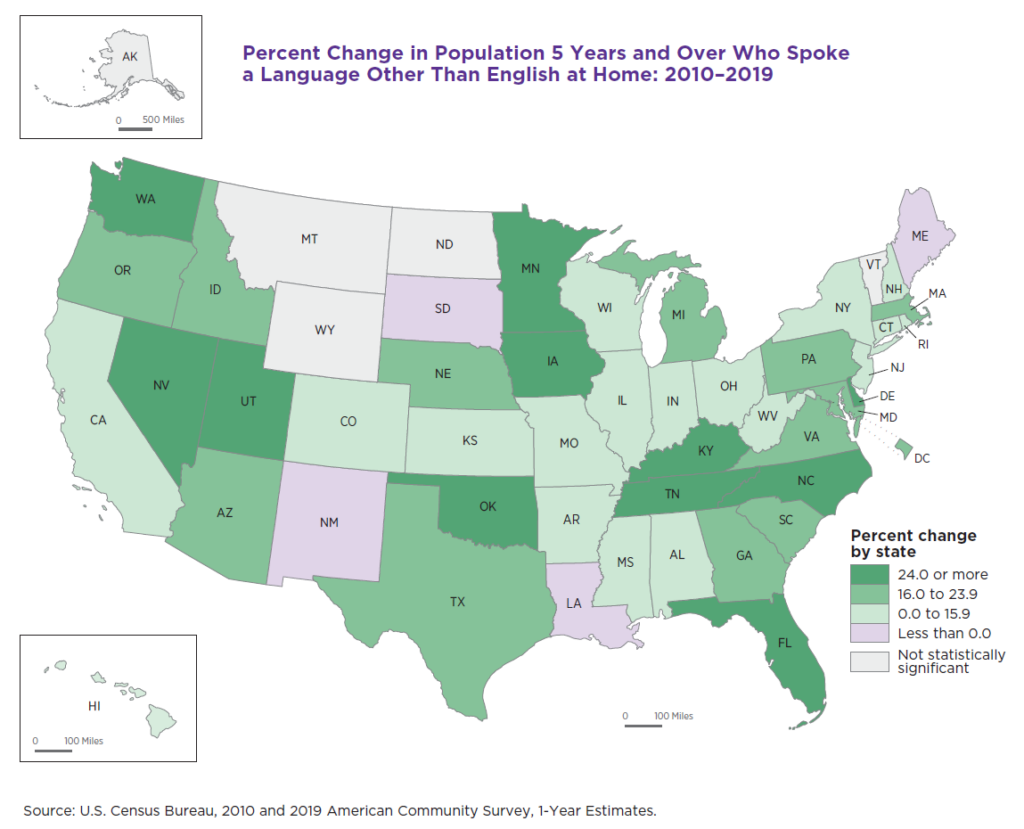

Due to greenhouse gas-induced climate change, not only are there increased risk to disasters, but consequently increased climate-displaced communities both within and across United States boundaries. Approximately 3.2 million Americans are already “climate migrants” due to flooding in the U.S. alone. Climate migration, whether internal or external, challenges and marks the importance of states tracking emerging languages and ensuring that emergency communications are translated accordingly. In 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that between 2010 to 2019, the population that spoke a language other than English increased nationally by 14 percent, but as shown in the map below, some states actually had a decrease while others had a significant increase. These changes can be due to both within and across border migration.

Therefore, language access policy should include resources to regularly survey emerging languages in areas with growing LEP communities. New York, for example, uses the ACS 5-year data to determine the top common languages spoken, but states should supplement such data as immigrants and refugees tend to be undercounted in the census. It would also be beneficial for any language access policy to explicitly state a minimum threshold for requiring translation services for certain languages. For example, a recently enacted Michigan law requires translation and interpretation services for languages spoken by LEP individuals that comprise at least 3% of the population or 500 individuals in the region served by the agency.

Beyond Language – Trust & Cultural Competency

Meaningful language access is more than translation and interpretation, especially in the emergency and disaster context. It is about effectively communicating critical information so people can make informed decisions and ultimately save lives. Research in risk communication shows that trust in the source of information and cultural competence in communication are crucial. Immigrants and refugees may have reasons to distrust local governments, ICE, federal agencies, and police. Therefore, communication from these official sources might not always elicit the expected emergency response.

To better understand a language access policy’s effectiveness, policymakers should consider setting standards for language access that measure accessibility based on cultural competence. Policies should also facilitate coordination with a network of trusted sources of information, especially from those representing various cultural, ethnic, and language backgrounds.

Language Access Justice – Accuracy, Speed & Literacy Access

True language access justice ensures that translation and interpretation services are both accurate and prompt. This is crucial in emergency management, where evacuation orders are urgent and timely translation of emergency information is vital. In a recent comment period on FEMA’s new rules for their Individual Assistance Program, several comments raised issues about translation accuracy and speed which caused LEP survivors vital recovery resources they were otherwise eligible for.

Additionally, while plain language laws and policies exist, highly technical terms in emergency communication still remain both in English and translated versions that are not accessible to all literacy levels. Inaccessible language reduces the ability of individuals to understand and therefore take appropriate action around emergency information.

Therefore, language access policies should include performance measures to track the speed, accuracy, and literacy accessibility of translation services. This includes tracking how quickly newly emerging languages are identified and incorporated into translation efforts.

Conclusion

As climate change intensifies climate disasters, lifesaving communication around emergency response, relief, and recovery must be accessible to all. Limited English speakers, some who are immigrants and refugees who have already been displaced by climate events, are more susceptible to further climate disasters in the U.S. due to the strong linkage between the exploitation of labor and exposure to hazardous environments. Successful language access policy requires investment in a central point of contact to coordinate diverse language access efforts. While language access policies exist across the United States, few make direct appropriations to fund a full-time coordinator explicitly in emergency management. Hawaiʻi’s new law serves as a model to embed language access into emergency management and coordinate a network of locally based and culturally competent language access providers across the state.

For more research and policy recommendations on language access in emergency management, read this report by the Natural Hazards Center and this resource page from the Language & Accessibility for Alert & Warning Workgroup.