In February the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized a new air quality standard for small particulate matter (PM) or what is commonly known as soot. The standard is for the pollutant termed PM2.5, which refers to particles less than 2.5 micrometers in size or about three percent of the width of a human hair. These small airborne solid or liquid particles are inhaled and penetrate deep into the lungs, contributing primarily to respiratory and cardiovascular health problems; there is also growing evidence of links to neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and varieties of dementia. PM2.5 is considered the most dangerous common air pollutant for health and is associated with as many as 200,000 excess deaths annually in the United States, many at exposure levels below previous EPA standards.

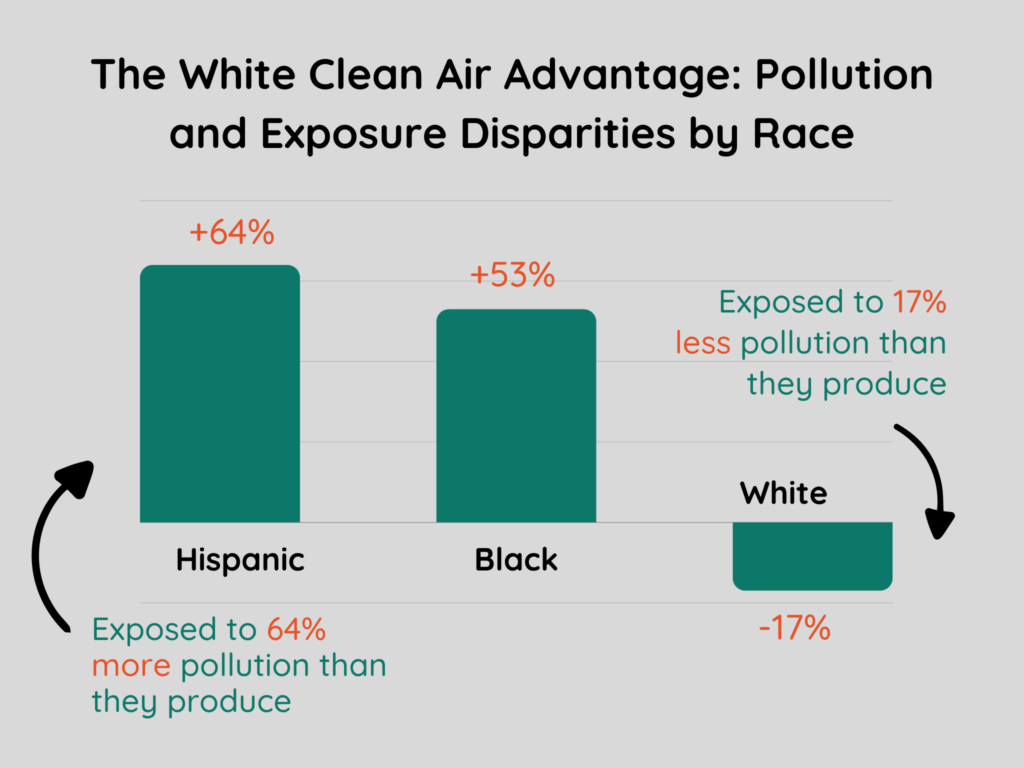

PM2.5 exposure disproportionately affects people of color. Those who are Black are exposed at a rate that is 54 percent higher than that of the whole population. One study found what it terms a white pollution advantage for PM2.5. It looked at racial disparities of exposure to PM2.5 compared to racial disparities of consumption. We graph the stark gaps in the illustration below.

It should be noted that these disparities persist even as broad swaths of the overall population continue to be exposed to unhealthy levels of air pollution for varying reasons, including a surge of 9 million people breathing too much PM2.5 in 2021, mainly due to the wildfires in the West.

What is the New Standard?

PM2.5 is primarily regulated for major stationary sources, such as power plants, factories, refineries, incinerators, and other sources. Regulation is based on a standard developed under the National Ambient Air Quality Standards program of the Clean Air Act (NAAQS). Along with five other common pollutants (nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone, carbon monoxide, and lead), the PM2.5 standard must be updated every five years. But the Trump Administration systematically disrupted the required PM2.5 update, resulting in a more than 10-year gap in the standard. This gap is exacerbated by a compliance grace period of two years under the new standard.

The new “primary” standard (meaning health-based) lowered the allowable concentration of the pollutant from 12 micrograms per cubic meter to 9 micrograms. This is the annual standard, meaning it is averaged over a year. The EPA projects that the new standard will prevent up to 4,500 premature deaths and 290,000 lost workdays, while generating up to $46 billion in net health benefits in 2032.

Environmental justice groups and the American Lung Association argued for a more stringent standard of 8 micrograms, based on scientific recommendations. All other aspects of PM regulation, including a 24-hour standard for PM2.5 and standards for larger particle, PM10 pollution, were left unchanged.

The EPA explained that it was comfortable in standing pat on the 24-hour standard for short-term exposure, which mainly affects infants, children, and elderly people with pre-existing lung and heart conditions. The current standard is scientifically sound and need not be tightened in addition to the annual standard, according to the EPA. The new rule, ten years late, made no pretense of being a comprehensive update or of being especially focused on protecting the most vulnerable populations affected by even limited exposures.

Mismeasuring Air Quality: Cumulative Impacts

Leaving aside the specific shortcomings of the new PM2.5 standard, more broadly, it is important to understand certain basic limitations in the design of how air quality is regulated by the EPA under the Clean Air Act.

Perhaps the most basic limitation is a standard-setting approach based on considering discrete health impacts of individual pollutants. As legal scholar and environmental justice advocate Deborah Behles points out, ozone, particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide are all chemically and physically related and are emitted from similar and often proximate sources such as power plants, fossil fuel combustion, and industrial processes. While each pollutant has its own health-based standard, in fact they interact in the air. Nitrogen oxides are a precursor to ozone, and nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide help to create particulate matter. Yet the standards for these pollutants do not account for the health effects of the other pollutants they help form in the ambient mix people breathe.

Behles has argued for “multi-pollutant” standards, which seems especially relevant for areas with multiple clustered pollution sources, of which there are many. One example is West Louisville. Louisville is the second-most polluted mid-size city in the country. However, eighty percent of this pollution is concentrated in West Louisville, where there are 56 toxic facilities and the population is 80 percent Black, with a median household income of $22,000. As a result of these conditions, the Black-white life expectancy gap in Louisville is approximately 12.5 years, and it is estimated that roughly three-fourths of this life expectancy gap is caused by pollution. West Louisville is part of Jefferson County, an area which is classified by the EPA as being in compliance with all of the NAAQS except 8-hour ozone.

Regulators should be able to ask if a facility’s allowable pollution may be more harmful if considered, not in isolation, but as one factor among many that may be affecting people’s health in the surrounding community. Without this, while a given facility may be deemed “healthy” by EPA standards, the same facility clustered among 15 others within, say, a 3- or 5-mile radius, is contributing to a total pollution level and a combination of pollutants that could be extremely unhealthy, even deadly, for vulnerable residents of the community, as in the case of West Louisville. Put simply, in communities with a high concentration of polluting facilities and infrastructure, and multi-pollutant effects, the air that people actually breathe is likely to be more toxic than might appear on paper according to the NAAQS.

The problem of multi-source air pollution is further compounded by fragmented statutes and standards that cover other forms of pollution and environmental risk besides ambient air pollution. These include air toxics, water pollution, hazardous waste, toxic chemical cleanups and storage, and more. While regulated separately, the reality is that multiple sources and types of pollution and environmental risk do not affect a given community or population in isolation from one another. Rather, they have combined, interactive, and additive effects over time that, in combination with socioeconomic and mental health stressors (including psychological and emotional effects of racism), result in significant health impacts and disparities that are a specific, complex byproduct of the places and the environments where people live. Other variables include changes in the built environment, such as a nearby highway expansion, or specific events, such as a weather disaster that damages a toxic storage site.

A Way Forward for Community Air Quality: Regulating Based on Cumulative Impacts

Environmental justice scholars and leaders have worked tirelessly to advance the idea of cumulative impacts as a better standardizing lens for regulating pollution, especially in socially distressed communities. As described in a recent EPA white paper, “cumulative impacts provide context for characterizing the potential state of vulnerability or resilience of the community, i.e., their ability to withstand or recover from additional exposures under consideration.”

Linking cumulative impacts analysis with the specific question of “additional exposures” or added burdens is clearly important in the face of accelerating climate impacts that could compound existing burdens. So too, certain technological climate solutions heavily promoted by Congress and the Biden Administration, such as carbon capture and storage, “clean hydrogen,” and “insourcing” of critical mineral supply chains are raising serious concerns from environmental justice advocates about added harms and risks for their communities. How will new burdens and benefits be meted out across different communities? In its first major report, the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council stated directly that the Justice40 initiative requires “100 Justice,” meaning that positive investments must be coupled with prevention of further harm in “historically harmed communities.”

From Standard-Setting to Cumulative Impacts-Based Permitting

As Behles notes, in fact the EPA has long recognized, studied, and taken steps to consider cumulative impacts analysis in air quality standard-setting. More broadly, the agency has worked to systematically identify legal and policy avenues for strengthening pollution regulation in disadvantaged communities.

In particular, the EPA has emphasized facility air permitting, which states control, as potentially providing authority and flexibility for decision making that accounts for cumulative impacts, such that regulators are encouraged or in some cases directed to broaden their focus from individual pollutants and facilities to the “total amount of pollution in a neighborhood,” as Nicky Sheats of the New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance has put it. However, even in recently promulgating a robust set of regulatory principles to promote environmental justice in air permitting, the EPA leaves no doubt as to the discretionary status of such principles, insisting that “[n]othing in this document is intended to impose or establish legally binding requirements and no part of this document has legally binding effect or represents the consummation of agency decision making.”

Fortunately, a number of states are moving ahead on their own with a more holistic approach, one that effectively “backstops” pollution control with significant changes in state permitting rules and authority. The critical innovation is incorporating cumulative impacts analysis as a requirement of the permitting process and as a binding factor in permitting decisions. In this way, states are stepping in where the EPA has stopped short despite years of research and consultation on cumulative impacts.

States Take the Lead on Local Air Quality

New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts have been among the first states to require cumulative impacts analysis when permitting new and existing facilities. These new laws place the burden of proof on permit applicants to show that the issuance or renewal of a permit will not increase cumulative environmental or public health burdens on already overburdened communities. These laws share common characteristics. In general, they require the project applicant to prepare an environmental justice impact statement that analyzes the environmental and public health burdens borne by the community; the impact statements are subject to public review and public hearings in the affected community.

Another critical innovation—and departure from the NAAQS approach––is geospatial targeting of decisions. Local pollution and the needs of specific communities are put at the center of regulatory evaluation and impact. The New York example is particularly compelling because it expands the reach of the state’s groundbreaking Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act of 2019 by adopting its definition of a disadvantaged community as one that “bears the burdens of negative public health effects, environmental pollution, impacts of climate change, and possess certain socioeconomic criteria, or comprise high-concentrations of low- and moderate-income households.” [Also important, New York’s disadvantaged communities are not subject to political choice; they are formally designated by a specially created stakeholder body advised by experts, the Climate Justice Working Group].

New Jersey’s Environmental Justice Law was the first-of-its-kind cumulative impacts law in 2020. The law, championed by Ironbound Community Corporation, New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance, and Clean Water Action, applies to major sources of air pollution, incinerators, sewage treatment plants, scrap metal facilities, landfills, and medical waste incinerators. After the preparation of an Environmental Justice Impact Statement, the applicant is required to hold a public hearing in the overburdened community and respond to all comments.

The State has different requirements based on whether the permits are for an existing or a new facility. The State can deny permits for a new facility that cannot avoid disproportionate impacts on an overburdened community unless the facility can show it serves a “compelling public interest.” To serve a “compelling public interest,” the facility must prove that it is essential to the overburdened community’s environmental, health, or safety needs. Advocates rightfully fear that this exception will be interpreted broadly to allow for future siting of polluting facilities in overburdened communities for critical infrastructure, such as public works projects.

Most notably, the New Jersey law is limited in how it applies to existing facilities. The State’s environmental regulators cannot outright deny permits for renewal or expansion of an existing facility. The Law also allows the State to “not issue a decision that would compromise the reasonable requirement of public health, safety, and welfare to the environment in the overburdened community,” which could encompass certain critical public facilities. Regulators can only apply new conditions on an existing facility, meaning overburdened communities will only see incremental improvements in their pollution burden.

Two years later, New York followed suit, passing its Cumulative Impacts Law. The law adds new requirements to the State Environmental Quality Review Act, requiring the State’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to prepare an Existing Burden Report as part of the environmental review process of a proposed project or action. Because the Existing Burden Report is now part of the larger environmental review process of a project, the public can participate in the scoping of the environmental review statement, provide comments on the statement and the Existing Burden Report, and provide input during public hearings.

New York’s Law gives DEC the authority to deny permits for new facilities. The State goes even further than New Jersey by providing DEC the authority to deny permit modifications and permit renewals if the existing facility significantly increases the pollution burden of a community. This is unless the DEC finds that the permit would “…serve an essential environmental, health, or safety need of the disadvantaged community for which there is no reasonable alternative.” Despite closing the door on permits for new polluting facilities, the law still allows the Department to issue permits for existing facilities that clearly serve an essential need of the community.

Unlike New York and New Jersey, Massachusetts’s new cumulative impacts law does not include criteria that would allow regulators to deny permits for either new or existing facilities based on the analysis conducted. Under this law, which goes into effect July 1, 2024, facilities will be required to conduct a cumulative impacts analysis (CIA) for a major source within five miles of an environmental justice community and one mile for minor sources of pollution. When conducting a CIA, the project applicant must evaluate 33 environmental, health, and socio-economic indicators to assess existing community conditions. Although the new law requires meaningful public involvement and evaluation of the CIA in the permit process, it does not give the State’s Department of Environmental Protection the authority to deny permits or mandate mitigation measures to approve new or existing permits.

While these innovative laws vary in stringency and effectiveness to reduce cumulative impacts in disadvantaged communities, they serve as helpful examples of the ways states are addressing the gaps in EPA rules and traditional permitting.

| New Jersey | New York | Massachusetts | |

| Legislation Passed | July 2020 | December 2022 | June 2021 |

| Implementation Date | April 17, 2023 | June 2023 | July 1, 2024 |

| Authority to deny permits for new facilities | Authority to deny permits, except where there is a “compelling public interest in the community where it is located…” | Authority to deny permits if the project will cause or contribute more than a de minimis amount of pollution to a disproportionate pollution burden on the disadvantaged community. | None |

| Authority to deny permits for existing facilities | No authority to deny permits for existing facilities. The law only allows for new conditions on permit renewals or facility expansions to protect public health. | Authority to deny permit unless the facility shows it “…would serve an essential environmental, health, or safety need of the disadvantaged community for which there is no reasonable alternative.” | None |

| Other important notes | First-of-its-kind cumulative impacts law | This law amends NY’s State Environmental Quality Review Act (the state’s “mini-NEPA” law), which applies to permit applications for a new proposed project, project modification, or project renewal | Requires the preparation and evaluation of a Cumulative Impacts Analysis Report for permit approvals. No authority to deny permits for new or existing facilities. |

Federalizing State Advances

As states have moved forward with incorporating cumulative impacts in permitting decisions, the fact remains that many states will not follow New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts on this path. Thus there is a broader need to fix this at the federal level, which will require legislation to change how permitting works under EPA rules.

The strongest such proposal is the Environmental Justice for All Act, introduced by Representative Raul Grijalva (H.R. 2021) in 2021 (and reintroduced in 2023). As the bill’s legislative findings state:

Potential environmental and climate threats to environmental justice communities merit a higher level of engagement, review, and consent to ensure that communities are not forced to bear disproportionate environmental and health impacts”….and “the burden of proof that a proposed action will not harm communities, including through cumulative exposure effects, should fall on polluting industries and on the Federal Government in its regulatory role, not the communities themselves.

The heart of the legislation establishes cumulative impacts analysis as a decision-making factor in air and water regulation. It does so by a bold step of amending both the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act, thus codifying in law that permitting authorities are required to conduct a cumulative impacts analysis of permit proposals and make decisions based on this analysis.

This law clearly departs from conventional agency discretion in merely “considering” cumulative impacts. With a given permit application, if there is no reasonable certainty that residents of the surrounding community and adjacent communities—or vulnerable subpopulations—will not be harmed, there are two courses of action. First, the permit can be modified to incorporate such standards and/or technological requirements as would be necessary to establish reasonable certainty that people will not be harmed; or second, if permit modifications are not sufficient to establish reasonable certainty that people will not be harmed, the permit or permit renewal must be denied. In addition, the legislation requires applicants with a history of violating environmental or other laws to submit a plan for complying with the Act after consulting with community members; if the plan is inadequate, the permit must be denied.

A Path Forward Toward Clean Air for All

In his 1970 State of the Union Address, President Nixon declared clean air to be a “birthright for every American,” and Congress’ response, in the Clean Air Act and other pollution control statutes, was to promise “virtually complete elimination of hazardous exposure to chemicals,” according to legal scholar Noga Morag-Levine.1 In fact, under the NAAQS and other pollution control programs, air quality has greatly improved, on average, across the country. But just as average income in a country can mask stark inequities and persistent poverty, average air quality categorically hides pollution inequities in places where disproportionate and cumulative exposures are not regulated as such and these translate into health impacts and health disparities affecting specific communities and populations.

The EPA’s updated PM2.5 standard, though more than 5 years late and not as stringent as it should be, is a welcome step forward in limiting the damage of this deadly pollutant. But in places affected by cumulative impacts of multiple sources of pollution, the EPA is not equipped to regulate for equal public health because of how standards are set and how air quality permitting fails to account for the “total amount of pollution in a neighborhood.” States have always had latitude, however, to go beyond EPA standards as long as this includes attainment of the applicable NAAQS in designated broad areas of the state. But with the shift toward including cumulative impacts analysis in permitting processes and decisions, we are starting down a new and better path such that communities can draw a clear line on added burdens and potentially gain a foothold for reducing existing burdens that continue to disproportionately affect their residents even as climate change is also bearing down.

- Noga Morag-Levine, Chasing the Wind: Regulating Air Pollution in the Common Law State (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003). ↩︎