An analysis of which states will be hardest hit and the financial impact

As the federal shutdown continues into its second month, households across the country are facing a looming crisis with uncertain funding for food and heating assistance—just as the weather is turning cold. Under pressure from the courts, the Administration has agreed to partially fund the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)1, but the allocated funds are not only insufficient but also delayed, and the Administration has repeatedly appealed court orders to provide full funding.2 Meanwhile, funding for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) is also expected to be delayed, and future funding levels are unknown, leaving households without much-needed support to pay for their winter heating bills.3

An end to the shutdown may be on the horizon, but funding timing and levels remain uncertain, and the disruption is laying bare the compounding effects of assistance shortfalls on communities across the US. Lack of access to these federal programs will have a devastating impact on families and children with lower incomes, and the economic ripple effect will be far-reaching—from mom-and-pop neighborhood stores to large retailers like Walmart, to energy providers and other businesses—as families who are unable to pay their bills are forced to make tough choices and trade-offs. The impacts of SNAP and LIHEAP funding delays vary by state, and below we show you where they will hit the hardest. Direct impacts of funding cuts will hit highest not necessarily in proportion to where need is the highest, but where states have done the best job at ensuring households that need assistance—particularly those with low-income, elderly, children, and disabled individuals—are enrolled in benefits programs. Given the Trump Administration’s ongoing efforts to limit eligibility and curtail funding and support for these programs—for example the entire LIHEAP staff was fired this spring and the Administration wants to eliminate its funding4—the threat to communities will remain even if an end to the shutdown is brokered.

SNAP provides benefits to approximately one out of eight Americans, reaching a total of over 22 million households a month.5,6 The program received $100 billion in funding in Fiscal Year (FY) 2024.7 Approximately 6 million households rely on LIHEAP, which provides energy bill assistance to low-income households and is critical to keep many homes warm through the winter months.8 LIHEAP’s annual funding is much lower than SNAP, at $4.1 billion in FY 20249—partly because it reaches fewer households total, but also because it is only available seasonally. This coming winter, LIHEAP may be an even more important lifeline than in previous years for households struggling to pay their utility bills: prices for methane gas, frequently used for heating, increased nearly 12% in the last year alone.10

While we don’t know the exact number of households receiving both LIHEAP and SNAP assistance, we do know that many households face difficult tradeoffs paying for essentials such as food and heating: in 2020, nearly 20% of households across the country reported reducing or going without food or medicine in order to pay their energy bills.11 A survey of LIHEAP recipients in 2018 found that 36% also went without food for at least one day12—meaning, even with heating assistance, recipients were still struggling to get basic necessities. How many more households will face these tradeoffs if heating and food assistance are not available? (Read The High Economic, Social, and Health Costs of Unaffordable Energy for more about these tradeoffs and their human impact.)

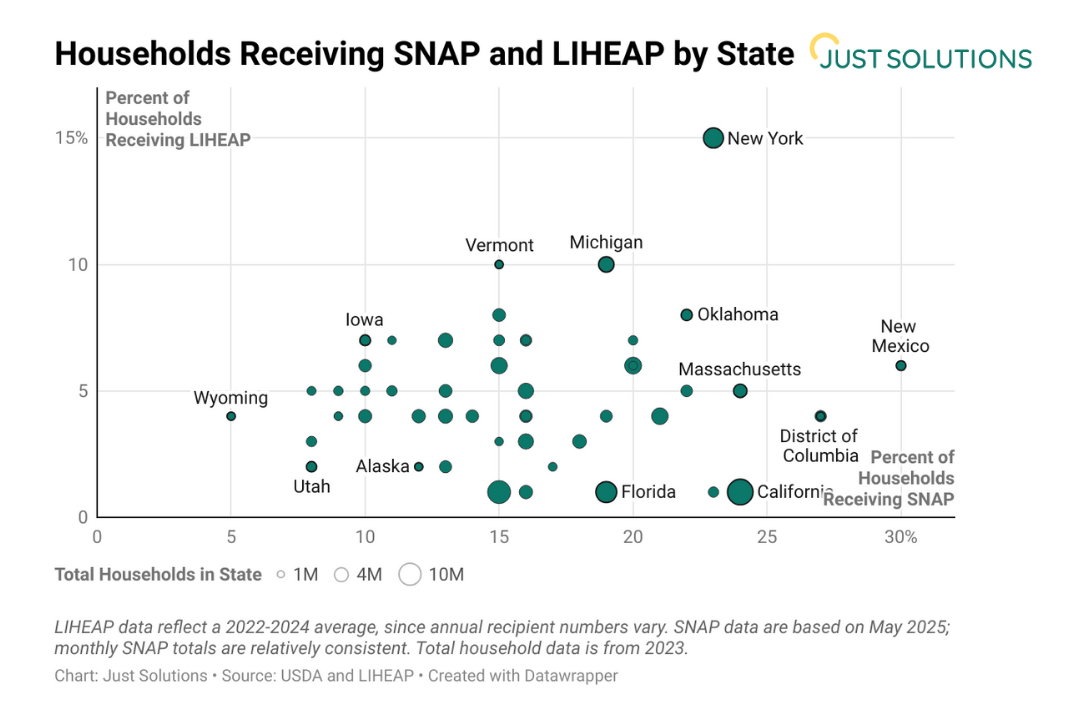

We mapped the percentage of households in each state receiving SNAP assistance and LIHEAP assistance to see where the delayed funding releases are likely to hit hardest. These are not necessarily where people will struggle the most with paying for food and energy, for a variety of reasons. Income levels, energy, and food costs vary significantly by state, and the number of eligible households that actually receive LIHEAP and SNAP varies widely from state to state. For LIHEAP, enrollment of eligible households ranges from 1% in Texas and Florida to 40% in Michigan and 51% in New York.13 Oregon has the third highest number of SNAP recipients per capita out of any state—not because it has a particularly high percentage of households in need, but because it has done a very good job at ensuring those households have access to benefits.14 So while need may be very great in many states with low enrollment levels as well, the areas mapped below are likely some of the places where food and energy costs this November will come as the greatest shock when federal assistance is delayed or unavailable.

Nearly 42 million Americans receive SNAP benefits every month, residing in 22 million households. Recipient households are smaller (1.9 inhabitants) than the US average (2.5), and nearly 80% include a child or someone elderly or with a disability.15 The states (including Washington DC) with the largest share of SNAP recipients include New Mexico (30% of households, and 21% of individuals); Oregon and Washington DC (27% of households); California and Massachusetts (24% of households); Nevada and New York (23% of households); Oklahoma and Louisiana (22% of households); Illinois (21% of households); and Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia (20% of households).

The states with the largest share of households receiving LIHEAP benefits are New York (15%); Vermont and Michigan (10%); Oklahoma and Wisconsin (8%); and Connecticut, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, New Jersey, South Dakota, and West Virginia (7%). As noted above, these numbers do not necessarily reflect which states have the highest energy cost burdens—just those who have the largest percentage of households enrolled in LIHEAP and which are likely to face the most shocks from federal funding delays or cuts. Some states may have high cost burdens but low LIHEAP enrollment, or have robust state-level energy assistance programs that are preferentially used instead of LIHEAP.

To get a better look at which states and households may see the most compounding impacts from SNAP and LIHEAP delays, we plotted the share of households in a state receiving LIHEAP and the share of households receiving SNAP. These are not always the same populations, but are expected to have some overlap. States that stand out include New York, Michigan, Oklahoma, and New Mexico.

The impacts of these funding losses hit low-income households first and foremost, but have ripple effects across the economy. SNAP funds support nearly $8 billion in purchases a month at grocery stores and farmers’ markets—and these stores will feel the pinch. One store in Massachusetts, for example, reports that 65% of its sales are paid for with SNAP benefits.16 Meanwhile, an inability to pay for energy bills results in mounting arrearages at utility companies—which in some cases may be passed on to other customers to pay.17 Unpaid arrearages can also lead to utility disconnections, which hold public health and safety risks, and may contribute to evictions, homelessness, and public health costs that increase the broader societal impact of unpaid bills.18

To see which states receive the highest cumulative LIHEAP and SNAP benefits—and a reflection of the magnitude of the economic disruption that may be caused if these benefits are cut off—we mapped 2024 annual funding allocations, by state, for LIHEAP and SNAP. Although we have data on monthly SNAP benefit levels, LIHEAP is provided as a block grant to states, each of which have different guidelines for allocation and the need for which may vary depending on how cold it is in a given month—meaning we do not know the exact demand for LIHEAP in November. However, this annual total gives a sense of how much each of these states relies on this funding.

A number of states are trying to fill the funding gap. Vermont—where 10% of households receive LIHEAP and 15% receive SNAP benefits—is using emergency funds to extend resources for food and heating assistance, even though the state will not be reimbursed by the federal government.19 However, Vermont’s extension for food assistance is only for 15 days, and many states may not have sufficient emergency funds to provide such funding at all. Even if they do, using up rainy day funds leaves states without a buffer against future emergencies—including, in particular, climate disasters, which already threaten to overwhelm state budgets in the wake of federal resilience and disaster funding cuts (which you can read more about here). States and local governments have also tried to increase protections for households while the shutdown—and funding delays—continue. The governor and utility commission in Pennsylvania, for example, reached an agreement with utilities not to disconnect LIHEAP-eligible households from electricity or gas service for the month of November.20 The mayor of Atlanta, Georgia, announced a moratorium on evictions and water utility shutoffs to mitigate the impacts of delayed SNAP benefits.21

But this federal shutdown highlights the pressing need to address the root causes of unaffordable living costs, rather than relying on uncertain and unreliable bill assistance programs. Households do, urgently, need bill assistance now to ensure that they have access to food and heating in the coming weeks and months. But they also need programs and policies that help create enduring change: programs that provide funding for energy efficiency and weatherization, for example, to reduce household energy demand and, in turn utility bills; and policies to increase utility accountability and rein in spending.

In our report Pathways for Action: Affording our Clean Energy Future we outline a suite of policies that states can pursue to systemically reduce energy bills while accelerating the transition to an equitable, clean energy future. These solutions start with emergency protections, now for households, including bill assistance and disconnection protections. But states also need to pursue equitable home decarbonization strategies, including energy efficiency, and utility reform to bring down spending, in order to provide lasting solutions. We also discuss funding and financing options —outside of increasing energy rates—to help provide the capital for these programs.

The delays—and potential funding cuts— to SNAP and LIHEAP, each alone, will have devastating consequences for the elderly, disabled, and those with lower incomes, and together will have a larger social and economic ripple effect. In the face of climate change—with hotter summers and extreme winter weather and more severe storms—the lack of federal assistance, access to weatherization, and clean, lower-cost energy makes matters worse. Rising food and electricity costs could drive larger-scale and further-reaching economic hardship. Addressing these impacts requires the resources, reach, and authority of the federal government. States cannot fill all these needs in any sustained way, but there are important actions they can take. The solutions exist; they require the public will and leadership to bring them into reality.

Footnotes

- Godoy, M. and Ludden, J. (November 3, 2025). SNAP benefits will restart, but will be half the normal payment and delayed. NPR.

↩︎ - Brown, M. (November 10, 2025). Trump administration seeks SCOTUS stay on paying full SNAP benefits. Politico. ↩︎

- Haigh, S. and Levy, M. (November 2, 2025). Government shutdown threatens to delay home heating aid for millions of low-income families. AP News,. ↩︎

- NEADA. (2025). LIHEAP Still Here, But Threats Loom. ↩︎

- v ↩︎

- SNAP reaches a slightly larger fraction of households (~17%) than individuals (~12%). ↩︎

- Jones, J. (2025). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) – Key Statistics and Research. U.S. Department of Agriculture. ↩︎

- 2022-2024 average. Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program. LIHEAP Data Warehouse. Accessed: November 3, 2025.

↩︎ - LIHEAP Clearinghouse. (2025). LIHEAP Funding for States and Territories.

↩︎ - U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (October 24, 2025). Consumer Price Index Summary. Accessed: November 3, 2025. ↩︎

- US. Energy Information Administration. (2022). Table HC11.1 Household energy insecurity, 2020. Residential Energy Consumption Survey, 2020. ↩︎

- APPRISE. (2018). NEADA National Energy Assistance Survey Report. Prepared for NEADA. ↩︎

- LIHEAP. Custom Report. LIHEAP Data Warehouse. Accessed: November 3, 2025.

↩︎ - Green, A. (2025). Why Oregon has 3rd highest percentage of SNAP recipients in U.S. The Oregonian. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2024). Characteristics of USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Households: Fiscal Year 2022 (Summary).

↩︎ - Smith, Tovia. (2025). If SNAP food aid is cut off, small grocery stores will also feel the pain. NPR. ↩︎

- Lawson, A.J.; Mills, C. (2023). Electric Utility Disconnections. Congressional Research Service Report R47417 ↩︎

- Makhijani, A. (2025). The high economic, social, and health costs of unaffordable energy. Just Solutions. ↩︎

- Cutler, C. (October 29, 2025). Vermont allocates emergency funds for food, fuel assistance amid federal shutdown. WCAX3. ↩︎

- Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. (November 5, 2025). Shapiro Administration Secures Commitment from Utility Providers to Protect Pennsylvania LIHEAP Recipients from Having Heat and Electricity Turned Off During Federal Government Shutdown. ↩︎

- Mayor’s Office, Atlanta, Georgia. (December 30, 2025). Mayor Andre Dickens Announces Eviction and Water Shutoff Moratorium to Support Residents Impacted by SNAP Lapse Amid Federal Funding Uncertainty. ↩︎