On December 2, 1984, as the city slept, 40 tons of deadly gas leaked from the Union Carbide pesticide production facilities in Bhopal, India. By sunrise, over 2,000 people were dead. Over half a million people in the villages and slums surrounding the plant were affected, including over 200,000 children and 3,000 pregnant women. Many survivors developed cancer, miscarriages, and other devastating long-term effects of toxic pollution that filled their air, soil, and waters. Multigenerational health and social impacts continue to be uncovered, with 15,000 to 20,000 premature deaths reportedly occurring over the next two decades after the gas leak. Today marks the 40th anniversary of the worst industrial disaster in the history of the planet.

As we reflect on lessons learned from the Bhopal tragedy and look to the outcome of the U.S. election, frontline communities across this country face imminent threats from the even greater weakening of government regulation of industrial polluters. A recent 2024 study in Nature has found that oil and gas industries in the U.S. currently leak far more methane than previously estimated. Last month, a Houston-based petroleum company, Phillips 66, was charged by a Federal grand jury with violating the Clean Water Act for allegedly dumping 310,000 gallons of industrial wastewater containing 64,000 pounds of oil and grease into the Los Angeles sewer system, more than 300 times the concentration of oil and grease allowed. Vigilant defense and well-coordinated advocacy at the local and state levels will be crucial to protect our communities and prevent devastating industrial disasters from further harming them.

Bhopal is the capital city in the state of Madhya Pradesh, in north central India. It is known as the City of Lakes. In the 1960s, India experienced rapid technological changes in its agricultural practices marking a transition from subsistence-based farming to large-scale commercial farming with modern technology when agriculture contributed to almost 50% of India’s GDP. Known as the Green Revolution, this new agricultural policy had far-reaching social impacts through technological innovations that continue to have damaging consequences, such as the mechanization of traditional farming and the introduction of high doses of pesticides and fertilizers.

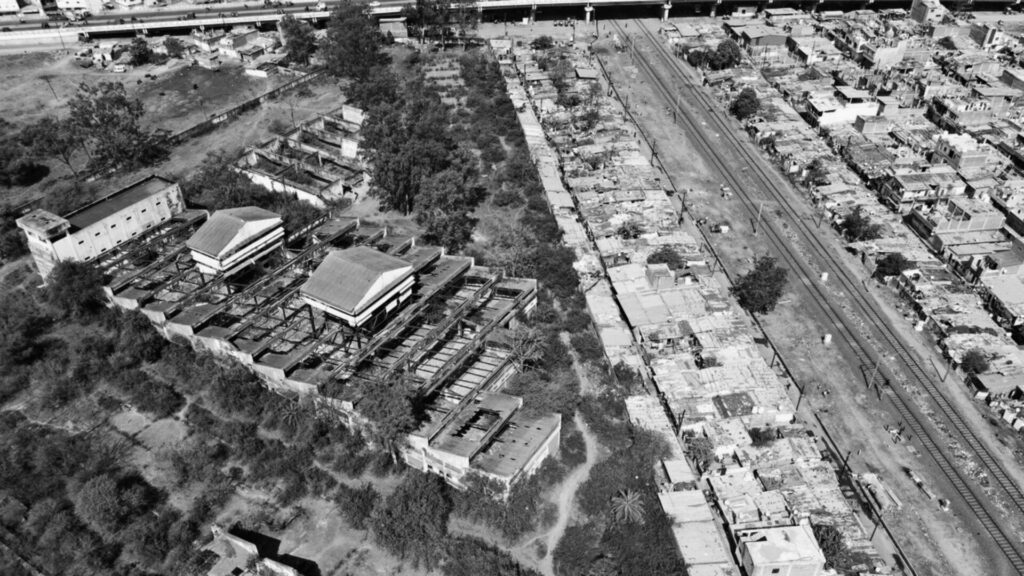

One such company that was part of this technological advancement, the Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL), majority owned by the American Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), established a plant in Bhopal in 1969 to produce pesticides for use in India to help the country’s agricultural sector increase its productivity. UCIL ran a plant for methyl isocyanate (MIC) production, the intermediate chemical necessary for a carbaryl-based pesticide. Records show UCC’s negligence and underinvestment in safety measures in the years prior to the gas leak led to a dangerous working environment and risks to the surrounding communities. Corporate profit and colonial mentality drove decisions that continue to have a devastating impact on the communities in Bhopal. This disaster was preventable, and there were clear warning signs that were ignored by the corporation:

- In 1976, local trade unions complained of pollution within the plant.

- In 1982, a phosgene leak exposed 24 workers, all of whom were admitted to a hospital. Phosgene was developed as a poison gas for use in World War I. Investigation revealed that none of the workers had been ordered to wear protective masks.

- During 1983-1984, leaks of MIC, chlorine, monomethylamine, phosgene, and carbon tetrachloride, sometimes in combination, were reported.

An estimated 700,000 people were affected from the Bhopal disaster, and now current and future generations are forced to deal with the environmental consequences. Locals struggled with debilitating health effects, environmental damage, and loss of livelihoods. A 2023 analysis published in the British Medical Journal documents these long-term intergenerational impacts, showing that men who were in utero at the time of the Bhopal gas disaster were more likely to have a disability that affected their employment 15 years later and had higher rates of cancer and lower educational attainment over 30 years later.

Four days after the gas leak, UCC chairman and CEO Warren Anderson, an American citizen, was arrested, released on bail, and flown out on a government plane back to the U.S. A lawsuit was initiated and a settlement reached in February 1989. Union Carbide agreed to pay US$470 million for damages, only 15% of the original settlement amount that the Government of India had asked for. This translates into $1,000 for each death, $500 to victims who suffered life-long injuries, and nothing for future generations that continue to experience long-term health impacts. With compensation of about $500, survivors have received about 4 cents per day to cover life-long injuries.

The Bhopal Gas Disaster was a horrific tragedy and painful reminder of whose lives matter more in this world. The enduring Global North-Global South structural inequities stem from centuries of colonial and imperialist systems of political dominance and economic exploitation. India’s government was no match for the U.S. and struggled to defend its citizens against U.S. global influence and control. Bhopal is a sobering lesson on the catastrophic consequences marginalized communities face.

As the U.S. heads into this next era of deregulation, gas leaks and industrial accidents are very likely to multiply, causing far greater social costs to frontline communities. States that are home to industrial sites should understand the potential risks and harms to their community members and prioritize measures to mitigate these. Formal public and community input should be built into state and local policy design processes with the aim of holding corporations accountable for developing and implementing stringent safety and health regulations, having public emergency and disaster response systems in place, and providing greater corporate transparency, including disclosures of associated health impacts and radius of impact. Pushing corporations beyond status quo standards and centering communities at greatest risk of industrial accidents will be the only way to prevent industrial accidents from the devastating consequences that extend far beyond the mortality and morbidity experienced in the short-term.